The COVID-19 pandemic dealt a devastating blow to low-wage workers, particularly workers of color. These workers suffered disproportionate job and income losses as sectors such as retail and food service navigated pandemic-related closures and reduced services. The pandemic also created fundamental shifts in the labor market, placing workers with low wages at greater risk of displacement and requiring them to learn new skills to compete for well-paying jobs.

Yet they face significant barriers to pursuing education and training to gain those new skills. And parents have the additional challenge of having to find and afford child care which has become even more difficult, given the pandemic’s damage to the child care sector.

Poverty levels are higher for parents with less educational attainment, while higher levels of education and training are associated with higher incomes and better employment opportunities. And higher levels of education and income for parents can translate into better outcomes for children.

Our new research explores the intersection of these issues: the importance of education and training in preparing low-income parents for a postpandemic labor market and the role of accessible, affordable child care in supporting parents as they pursue their education and gain new skills. We use the Urban Institute’s Analysis of Transfers, Taxes, and Income Security (ATTIS) microsimulation tool to model an alternative policy scenario in which child care subsidies administered through the federal-state Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) were more accessible to parents seeking to enroll in education and training programs.

Current restrictions in the CCDF program prioritize parents who work

CCDF helps families with low incomes pay for child care so they can work or go to school. Yet parents needing assistance to go to school are less likely to get help than parents who need assistance to work.

There are three reasons for this. Funding levels for CCDF are sufficient to serve only a fraction of those eligible for help (PDF), forcing states to make difficult decisions about who receives assistance. Many states have established additional eligibility restrictions for student parents to receive assistance for child care during hours they may be in school. These restrictions may include requiring student parents to work while going to school, setting time limits on assistance, and limiting the number or type of degrees parents can seek.

Finally, states are less likely to pay for some types of care often needed by student parents. Student parents are more likely to have irregular school and work schedules that don’t conform to the traditional hours of operation offered by licensed child care programs (which are more likely to support a 9–5 weekday work schedule). As a result, student parents often rely on multiple child care arrangements, including relatives, friends, or smaller home-based providers more likely to provide care during nontraditional and irregular hours. However, these providers may not be regulated by the state and can face additional challenges to being part of the subsidy system.

What did we learn when we modeled an expansion of child care subsidies for these families?

What would happen if we addressed these three constraints? What if there were enough funds to serve any eligible person who wanted a subsidy, if work requirements were eliminated and other limits were reduced, and if parents could use the funds to pay for care that suited their needs?

To model this hypothetical policy expansion, we first examined the participation of student parents under existing policy by using a combination of administrative data from the CCDF program for 2018 (the most recent year for which we have detailed data) and data simulated by ATTIS. We then used ATTIS to compare that result to what would have happened in 2021 under a policy that reduced restrictions described above. Here is what we found:

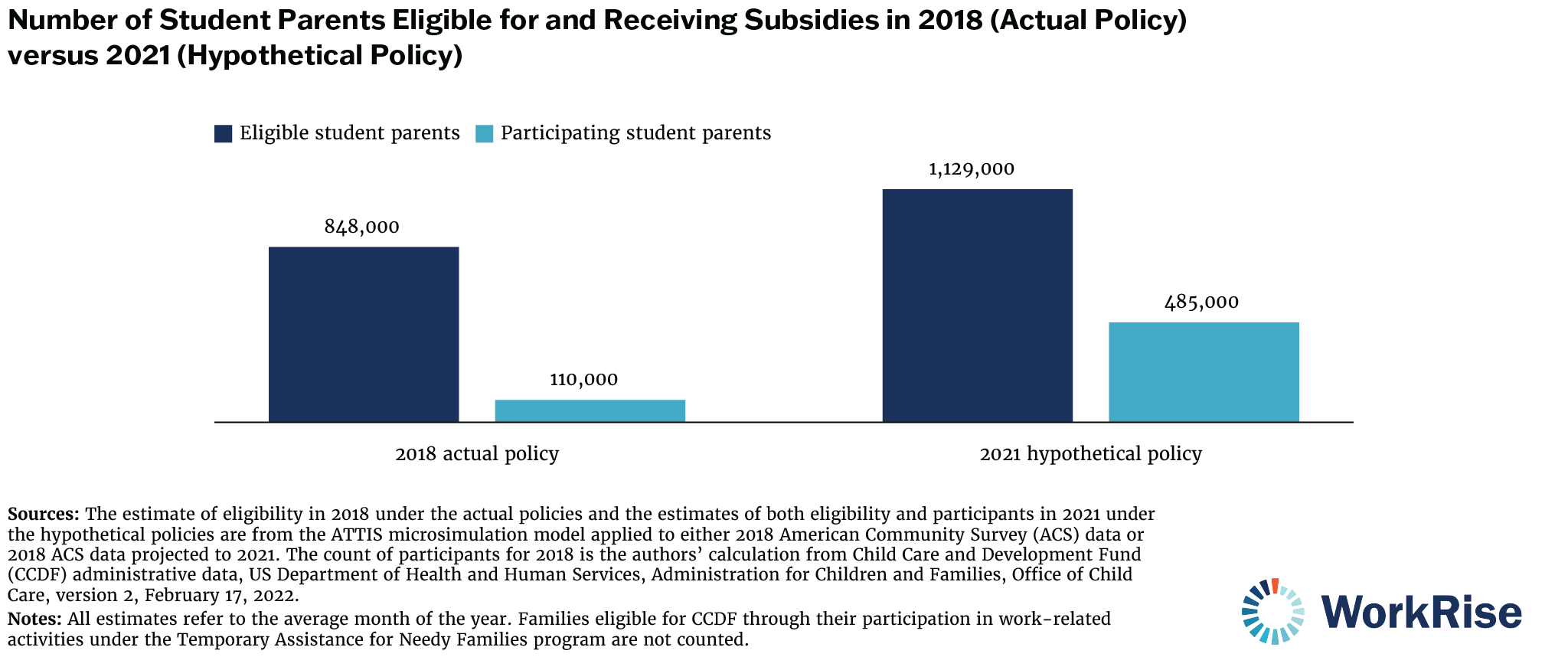

- In 2018, an estimated 848,000 student parents were eligible for CCDF subsidies under existing state policies, and an estimated 110,000 student parents received subsidies. A hypothetical policy expansion in 2021 would have increased the number of eligible parents to 1,129,000 and the number receiving subsidies to an estimated 485,000. As shown in the figure below, this is a more than fourfold increase in the number of student parents receiving subsidies.

- This set of policy and funding changes would result in significant support for student parents of all races and ethnicities, but about 60 percent of the families served under this new scenario would be Black, Hispanic, or Asian American or Pacific Islander.

- Not all student parents would end up completing a credential, as they still face myriad other challenges unrelated to child care. But when we look at the families we project (based on a specific set of assumptions) would complete the credential because of the child care assistance, we estimate their earnings would be 26 percent higher in the year after the credential was completed than would otherwise have been the case. Child poverty in these families would decline by nearly 4 percentage points.

- Given that these estimates are just for the year after the parent earns their credential, these gains would likely grow as families continued on their earning trajectory. If this policy expansion were to remain in effect, the total number of children raised out of poverty would also grow each year as more parents completed their credential.

What can policymakers do to expand access to child care subsidies to student parents?

These findings suggest that policymakers interested in supporting parents earning low wages who want to improve their skills through education and training could consider the following steps to help student parents become eligible for and use child care subsidies:

- Increase funding to allow child care assistance to go to student parents. This issue is the most challenging, although expanded child care investments continue to be debated by federal and state policymakers. Concerns over child care availability and affordability continue to be at the forefront of discussions about achieving an equitable economic recovery.

- Reduce states’ extra eligibility restrictions for child care subsidies for student parents, such as work requirements and time limits. We suggest states work directly with student parents to better understand their constraints and with workforce development experts to understand the costs and challenges such restrictions create for student parents.

- Ensure student parents can use their subsidies to purchase the care that meets their nontraditional scheduling needs. Student parents are likely to need a variety of child care options, including care provided by relatives and friends and other home-based providers more likely to offer care during nontraditional schedules. Supporting these options will require policymakers and child care experts to identify ways to best protect children’s health and well-being in such settings while ensuring that protections respect the different demands of caring for children during nontraditional hours, the ways such providers may differ from licensed group settings, and these providers’ important role in supporting parents and children.

The pandemic raised our awareness of both the challenges workers with low wages face in improving their employment and economic mobility and child care’s critical role in helping parents complete their education and seek better employment opportunities. Our analysis suggests reducing barriers parents with low incomes face in securing child care assistance to support their education and training could make a difference in their future economic well-being and the well-being of their children.

Learn more:

Implications of Providing Child Care Assistance to Parents in Education and Training (report)

Expanding Child Care Subsidies to Parents in Education and Training (fact sheet)

Sellwell/Shutterstock