Last month, Colorado voters approved a new paid family and medical leave policy that provides up to 12 weeks of paid time off to workers who need time away from work to care for a new baby, a seriously ill family member, or their own serious illness. Colorado joins eight other states (PDF) and Washington, DC, as jurisdictions with public paid family and medical leave programs.

Colorado’s paid leave legislation ran aground in the state legislature last year, but the ballot initiative passed with a 57 percent majority, making it the first in the nation to approve paid leave via popular vote rather than legislative action. Recent polling (PDF) suggests paid leave receives strong support on a national level, with 79 percent of voters favoring a national paid family and medical leave policy.

Starting in 2024, workers in Colorado will be eligible to receive a percentage of their salary—not exceeding $1,100 per week—when they take parental, caregiving, or medical leave. Workers become eligible for the program after earning $2,500 in wages in the state. Once workers have remained with an employer for at least 180 days, their jobs are protected when they take paid leave. Like the other existing state programs, Colorado’s is a social insurance model, where workers and employers each contribute a small premium—in the case of Colorado, 0.45 percent of the workers’ wages—into a statewide fund. Like the other existing state programs, Colorado’s new benefit is also portable, as access to wage replacement is not premised on tenure with any sole employer.

With 10 state-level paid family and medical leave programs in various stages of implementation, the United States is currently a fantastic laboratory of policy experimentation. The burgeoning field of research on the effects of these new paid leave policies has the potential to meaningfully shape future policy in a way that benefits not only workers but also firms and the economy as a whole. States’ experiences can inform the development of federal policy, as they have with the FAMILY Act, a proposal that draws upon the policy design of many successful state programs.

And COVID-19, which is surging and showing no signs of abating, adds urgency to the need for a federal paid leave policy to cover workers—particularly those in health care, education, retail, and other industries with high person-to-person contact—if they or a family member get sick. A recent analysis of administrative data from California and Rhode Island shows claim rates for medical and caregiving leave surged to unprecedented levels in early March, suggesting state paid leave programs were responsive to workers and their families early in the pandemic.

Without a federal paid leave program, gaps in access will persist

Although a growing number of states now have paid family leave programs, the US is one of few countries in the world without a permanent federal program. The 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act guarantees eligible workers a right to job-protected unpaid leave, and the emergency paid family leave protections provided under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) expire at the end of the month. (To date, congressional interest in extending the paid leave protections provided by the FFCRA in the next economic relief package remains ambiguous.)

In the absence of a new federal paid leave program, workers in the 41 states without state policies have access to leave only if their employer choses to provide it. Nationally, just 21 percent of the civilian workforce has access to dedicated paid family leave, but roughly 89 percent have access to unpaid leave for these purposes, according to the most recent US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Compensation Survey of employers.

In general, employers are unlikely to voluntarily provide leave unless they believe their employees value it and that it will help them attract and retain higher-skilled workers (PDF). Rigorous surveys (PDF) of businesses in states with paid family leave programs find that, regardless of size or industry, employers are generally supportive of state paid leave policies and report few difficulties covering work when employees are on leave.

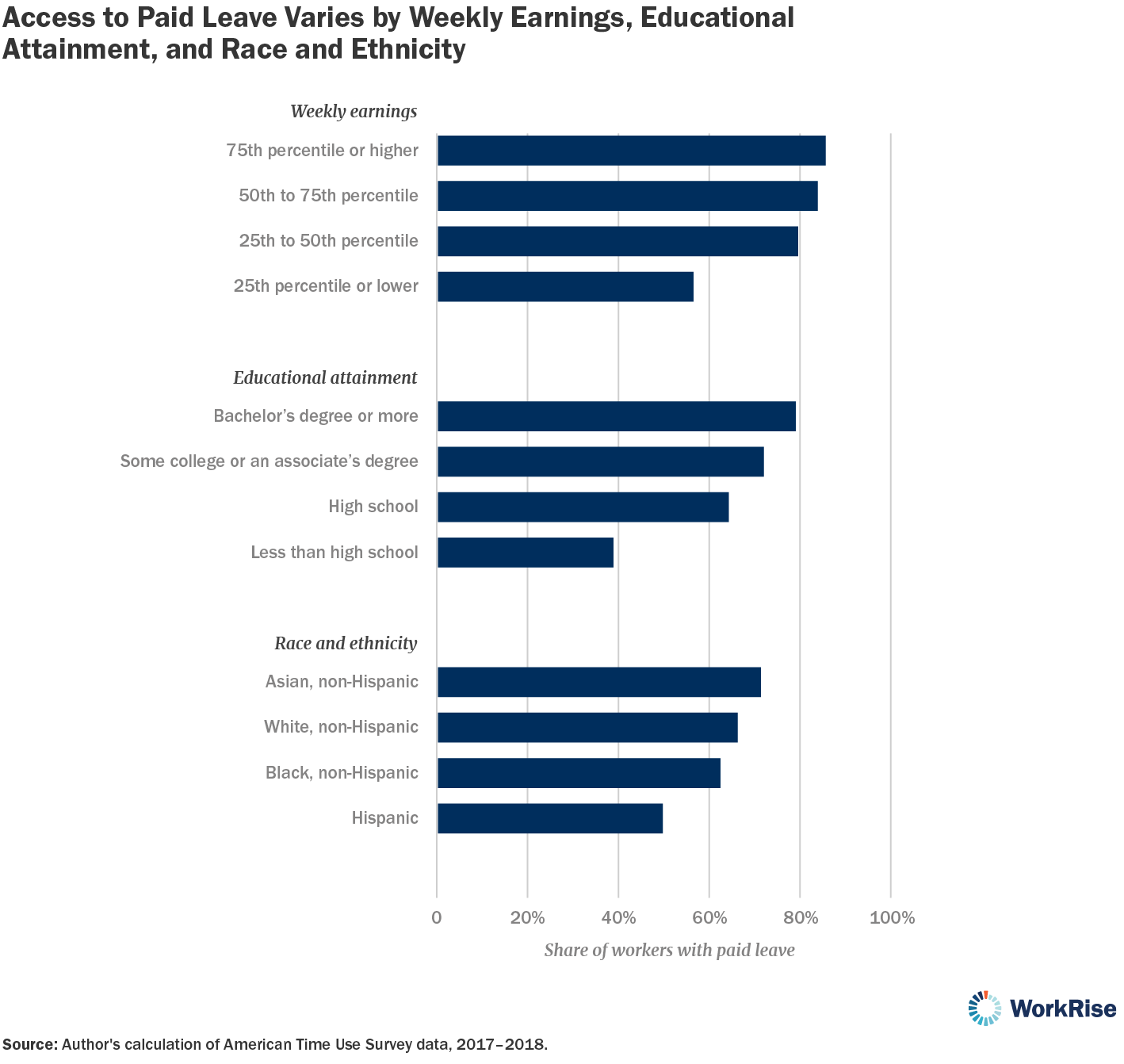

Who has access to paid leave? Workers with high earnings and more educational attainment are far more likely than those with low earnings and less educational attainment to have access to paid family leave, according to my forthcoming analysis of responses to the American Time Use Survey. Eight-six percent of wage and salary workers with earnings in the top quartile have access to paid leave, compared with 56.6 percent in the bottom quartile. Nearly 80 percent of wage and salary workers with a bachelor’s degree or more education have access to paid family leave, compared with just 64.0 percent of those with a high school diploma and 38.9 percent of workers who did not graduate from high school.

Disparities also emerge when comparing those with full-time versus part-time work. Although 77 percent of all full-time wage and salary workers have access to paid leave, just 23.3 percent of part-time workers report access. And the vast majority of workers in alternative work arrangements—including gig and contract workers—do not currently have access to paid leave benefits in the absence of portable public benefits programs, like the one passed in Colorado. Access to paid leave is also highly stratified by race and ethnicity. Just under half of all Latinx workers have access to paid leave, compared with 62.6 percent of Black workers, 66.3 percent of white workers, and 71.5 percent of Asian workers, according to my analysis.

What we know about paid leave’s impact on labor market outcomes

Evidence from states with established paid family and medical leave programs suggests that these policies can positively affect a range of labor market outcomes, including labor force participation, hours worked, and earnings trajectories, particularly among women who take paid parental leave.

California was the first state to implement a paid leave policy and has expanded the program several times since its adoption in 2004. California’s program—like Colorado’s policy—includes provisions not only for maternity leave but also for paternity leave, leave to care for a family member with a serious illness, and leave to attend to one’s own serious illness.

Multiple studies using both administrative and survey data from California’s program find that paid family leave leads to sizable increases in usual weekly hours for employed mothers and that mothers’ wage incomes may have increased as well. Another study of California’s program suggests paid leave plays a key role in stabilizing family incomes after the birth of a child, especially for low-income families. Among mothers of 1-year-olds, the study found the state’s paid leave program decreased the risk of poverty following the birth of a child by more than 10 percent.

Well-designed public programs can expand coverage to workers earning low wages, and they can be a powerful lever for equity in access. For instance, the introduction of paid family leave policy in California doubled the overall use of maternity leave, with particularly large increases for disadvantaged women. Use of maternity leave increased threefold for mothers without a college degree (from 2.4 percent to 7.7 percent), more than fivefold for those who were not married (from 1.9 percent to 9.4 percent), and sevenfold for Black mothers with new infants (2.0 percent to 13.7 percent).

Much of what we know about paid leave specifically centers parental leave. Our understanding of how other forms of paid leave—caring for an ill family member or taking medical leave for oneself—affect labor market outcomes is limited. Solid evidence on the role of paid parental leave in longer-term labor market outcomes may or may not translate to different forms of leave. Although the caregiving needs for a healthy newborn are relatively predictable, caring for a sick family member or oneself is less predictable and can range from short- to long-term, depending on the medical condition.

The majority of working parents report that work-family balance is a significant challenge. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised new caregiving challenges by exposing the fragile web of supports that existed before the pandemic. As we rebuild from the devastation of COVID-19, we can begin in the near term by extending the first-ever emergency paid leave protections contained in the FFCRA to combat the pandemic and help workers and businesses. From there, we can take a cue from states to create an evidence-backed, permanent, national paid family and medical leave program to support family caregiving and long-term economic security and mobility for workers and their families.